THE UNDERLYING CAUSES FOR SOCIAL TURMOIL WITHIN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

INTRODUCTION:

As long as the United States had a homogeneous population that consisted of the same northern European heritage, and relatively equal intelligence among the white ethnic Europeans, we could rally around a common theme, a common purpose. Yet today, we are a nation of fractions, where the parts have become more important than the whole. In order that we may understand better, we must remove ourselves, at least partially from the present and place ourselves into the past. We must remove the decades of forced propaganda to a time of original meaning, of original thought, to the genius that realized the requirements of making a nation. This text will attempt to educate the reader in an approach similar to solving a picture puzzle.

I have extracted quotations from the brightest in our world yesterday and today. The form of government we live under will be analyzed in summary, as will each of the major different groups of people living in this pluralistic, multi-cultured, multi-racial geographic land mass. After conclusion, much of the puzzle will still be missing, however, hopefully there will be enough of the picture showing to give the reader a reasonable idea of the problems underlying the current and upcoming social upheaval in America. I hope it will shed adequate light for the reader where none existed before. It certainly was a learning experience for me, read perhaps 1,000 books on race, past civilizations and Christianity. Kent Crutcher, CPA, MBA, 1989

Chapter 3

THE AFRICAN

Modern Images of Ancient African People

STATE OF AFRICAN/AUSTRALIA CIVILIZATION, EARLY EUROPEAN CONTACT, (1820ish, exploring inner Africa for the first time – pre-White man contact, the explorer diaries)

Dr. John Baker was Emeritus Reader in Cytology at Oxford University and author of nine books on biological subjects while a professor there. Baker’s book “Race” is the definitive text on this subject, from an academia perspective. From Arthur Jensen, the father of modern IQ research: “A most impressive display of profound scholarship and vast erudition in every main aspect of this important topic. Recent studies of racial differences in cognitive and behavioral characteristics have generally overlooked or belittled the biological, anatomical, physiological and evolutionary lines of evidence which are highly germane to this discussion. As a noted biologist, Baker provides the essential basis upon which any objective, rational, and scientific discussion of racial differences must proceed”.

John Baker’s “Race”, 1974, 600 pages

Baker quotes Kant and Hume to state the "18th century mentality" of the Negro. "The Negroes of Africa have received from nature no intelligence that rises above the foolish. Hume invites anyone to quote a single example of a Negro who has exhibited talents. He asserts that among the hundred thousands of blacks who have been seduced away from their own countries, although very many of them have been set free, yet not a single one has ever been found that has performed anything great whether in art of science or in any other laudable subject; but among the whites, people constantly rise up from the lowest rabble and acquire esteem through their superior gifts. The difference between these two races of man is thus a substantial one; it appears to be just as great in respect of the faculties of the mind as in color."

Amabed, an early Indian explorer of Africa, writes of the Negro (Hottentot) prior to mass contact with the white world, "These people do not appear to be descendants of the children of Brahma. Nature has given to the women an apron formed from their skin; this apron covers their joyau, of which the Hottentots are idolatrous...The more reflected on the colour of these people, on the chucking they use instead of an articulate language to make themselves understood, on their face, and on the apron of their women, the more I am convinced that these people cannot have the same origin as ourselves. Our chaplain claims that the Hottentots, Negroes, and Portuguese are descended from the same father. The idea is certainly ridiculous."

Lord Monboddo, a Scottish lawyer and African explorer speaks of the "ouran outangs" which were really the chimpanzee. "They are exactly of the human form, walking erect, not upon all four...they use sticks for weapons; they live in society; they make huts of branches of trees, and they carry off negro girls, whom they make slaves of, and use both for work and pleasure...But though from the particulars mentioned it appears certain that they are of our species, and though they have made some progress in the arts of life, they have not come the length of language." What surprised Mondoddo was not that they could not speak, but that they could not learn to speak. He agreed with Rousseau in rejecting the opinion that speech is "natural" to man. "Now if we can get over that prejudice," he says, "and do not insist, that other arts of life, which the Ouran Outangs want, are likewise natural to man, it is impossible we can refuse them the appellation of men." Edward Long, the historian of Jamaica, agreed with Rousseau and Monboddo in attributing intellectual powers to the anthropoid apes. "Nor for what hitherto appears, do they seem at all inferior in the intellectual faculties to many of the Negro race. He supposed that the oang-utan (the chimpanzee) was in a close affinity to man."

Baker continues, "Since the thirties of the present century there has existed an almost world-wide movement intended to foster belief in the equality of all human ethnic taxa. There can be scarcely any doubt that the impulse for this movement came from intense feelings aroused by the persecution of Jews under the Nazi regime." On the other hand Baker notes a recognized Frenchman, Gobineau, who believes that decay of religion, fanaticism, corruption or morals, luxury, bad government, despotism all are not the cause why great civilizations seemed destined to decay. He also rejects racial equality as a reason for the decay. ""I reject absolutely," he writes, "the type of argument that consists in saying "Every Negro is foolish," and my principle reason for doing so is that I hold myself at a hundred leagues from such a paradox." Gobineau also entirely rejects Ben Franklin's jib that the Negro is an animal that eats as much as possible and works as little as possible." "It appears to me too unworthy of science to dwell upon such futile arguments."

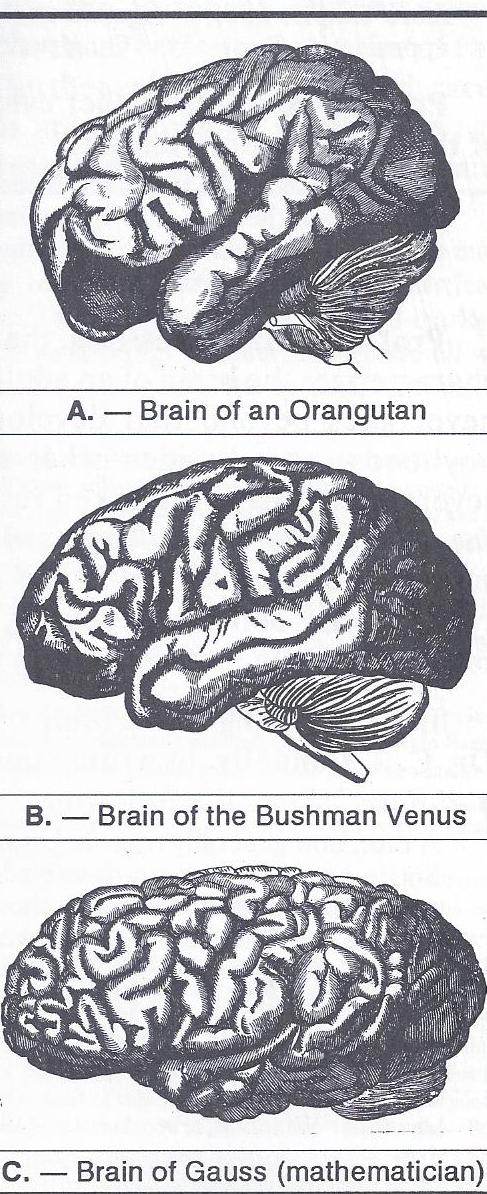

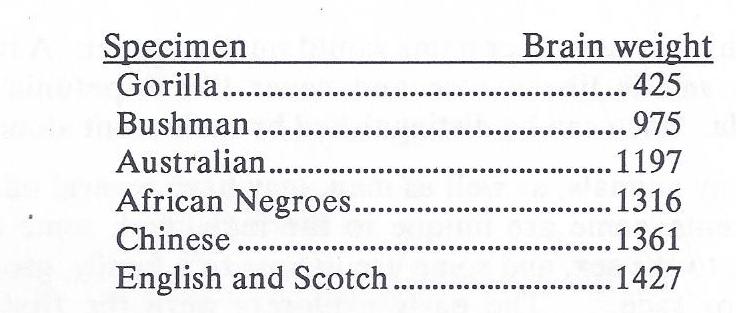

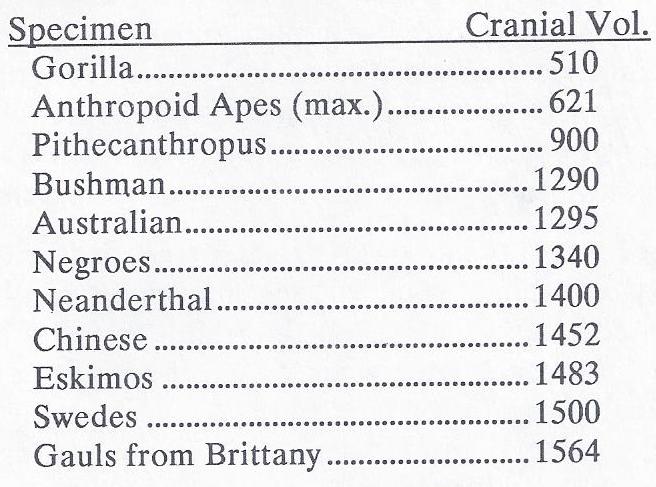

The Australids (aborigine in Australia). The capacity of the brain-case is small, about 1,290 on the average. The corresponding figure for the skulls of the Anglo-Saxon invaders (500 A.D.) of Great Britain was about 1,540 ml; of Peking man about 1,075; Java Man's is estimated at only 860 ml. In most ethnic taxa of man one can point to a few primitive characters, not possessed by certain other taxa. The Europids, for instance are primitive in the shape of the scalp-hair as seen in transverse section, and some of the Europid sub races are primitive in their dolichocephaly; but the Australids are exceptional in the number and variety of their primitive characters and in the degree to which some of them are manifested. In this chapter twenty-eight such characters have been mentioned. It is questionable whether any other ethnic taxon of modern man shows so many resemblances to Pithecanthropus and to more remote ancestral forms.

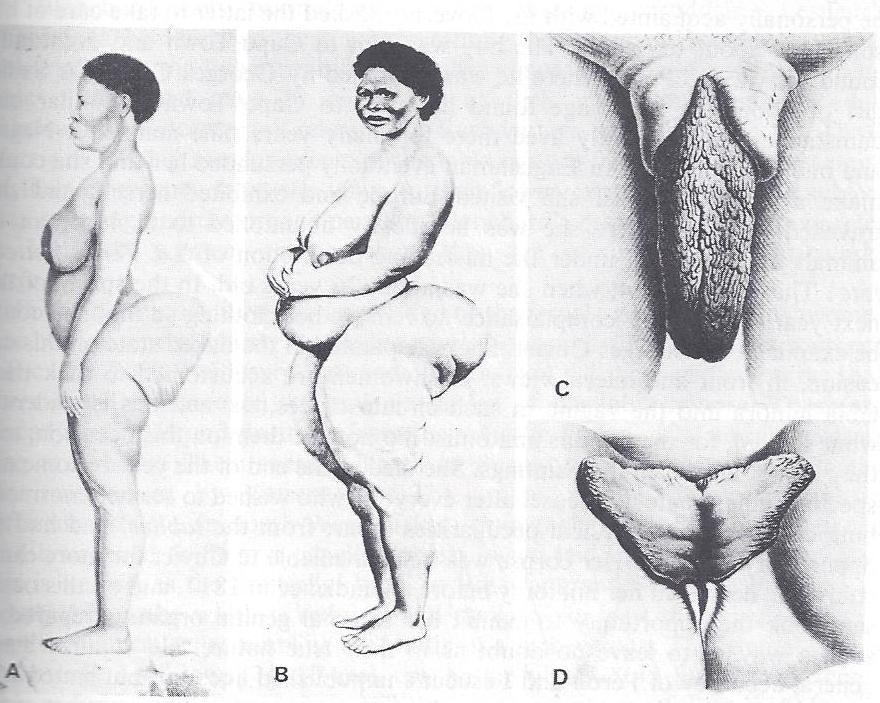

The Sanids (Bushman of Africa). Two reasons underlie the choice of the Bushmen of southern Africa as the subject of a chapter in this book. First, they are very different in physical characters - indeed in certain respects astonishingly different - from both Europids and Australids, and thus show particularly clearly how wrong it is to suggest that there are few differences between races, apart from skin-colour. Secondly, the Bushmen provide a good example of the influence of paedomorphosis in the evolution of certain ethnic taxa of man (not fully evolved)." "It is safest to say simply that most adultv Sanid skulls are small, having a capacity between 1,250 and 1,330 ml.” Undoubtable both brains show an infantile or foetal leaning. They have to themselves this peculiarity from other races', he wrote, that most of them (women) possess finger shaped appendages, always double, hanging down from the private parts; these are evidently nymphae (labia minora)." (In another way of stating this, is that the insides of a woman's privates' are hanging out anywhere from a half to six inches. At a distance, it resembles a male organ - kc).

The Negrids (Negroes). The penis is very long and rather thick when not erect, but this may perhaps be a general character of the Negrids. Negrid king complained to him of the English, who were the cause of the stagnation of the slave-trade. Samuel Baker, who subsequently led an expedition to suppress the slave-trade in the Sudan and the region of the great lakes wrote on this subject: ".... the institute of slavery... is indigenous to the soil of Africa, and has not been taught to the African by the white man, as is currently reported, but...has ever been the peculiarity of African tribes...It was in vain that I attempted to reason with them against the principles of slavery they thought it wrong when they were themselves the suffers, but were always ready to indulge in it when the preponderance of power lay upon their side." Livingstone describes how the king of the Balunda would organize an expedition to pounce on an unsuspecting village in his own territory, kill the headman, and sell every other inhabitant to a Negro slave-trader; or, if some of the people were too old to be useful as slaves, they were murdered, lest they should become troublesome afterwards by resorting to magic to avenge the attack on their village. Slavery thus stands at the junction of this chapter with the next. It was undoubtedly indigenous, but foreign traders greatly increased its extent. Negrids who had been accustomed to sell slaves to others of their race were just as willing to sell them to foreigners. Indeed, as Baker remarks, "all the best slave hunters, and the boldest and most energetic scoundrels, were the negroes who had at one time themselves been kidnapped." A commerce had existed, new buyers had arrived. A remarkable feature of slavery was its acceptance, in certain cases by those who were subjected to it. You engage one of them as a servant, and you find that he considers himself your property. They have no independence about them. They seem to be made for slavery, and naturally fall into its way. There is strong contrast here with certain other ethnic taxa of man, such as the Sanids (Bushman), whom it has been found almost impossible to enslave."

Canoes provided transport on lakes and rivers. They were made by excavating large trees, for, as Schweinfurth remarks... no people of central Africa seems to have acquired the art of joining one piece of wood to another, so that the craft of cabinet-maker may be said to be unknown. The wheel appears to have been unknown throughout the secluded area. Not only is there no record of its use in pottery or the grinding of corn, but no pivoted circular object, made by Negrids, is anywhere mentioned in the works of the explorers. All the principal domestic animals of the Negrids with whom we are concerned were introduced to them in an already domesticated state.

Adultery was almost unknown among the Zulu, as a result of the severe penalty imposed. Unmarried Zulu were not forbidden by custom or law to indulge in a form of sexual intercourse with one another, but they were not permitted to have children. This was avoided by a practice called ukuhlobonga, described by Fynn as the act of cohabitation on the outward parts of the girl between the limbs. Concubinage was permitted in certain tribes. Chaka (a Zulu chief) had at least five thousand concubines. They lived in several separate seraglios, where decorum was observed, Fynn tells us, as exactly as in any European palace. Concubines were not permitted to have children.

"Music and dancing played large parts in the social life of the Negrids almost everywhere in the secluded area." Speke, on the contrary, remarks that Negroes are mentally incapacitated for musical composition, though as timists they are not to be surpassed." The explorers did appreciate the virtuosity of Negrids as executant musicians. It was revealed by their precision in timing and accuracy of pitch, whether of voice or tuning of instruments. The capacity to sing in tune and in time seems to have been almost universal among the tribes visited by the explorers. The only striking exception to this generalization was provided by the Bongo whose singing at one time suggests the yelping of a dog and at another the lowing of a cow...everyone without distinction of age or sex...yelling, screeching, and bellowing with all their strength. Music seems everywhere to have played a large part in the lives of the people, and in some cases it utterly absorbed their attentions for long periods. Schweinfurth, from his own experience, was half inclined to believe Piaggia's statement that a member of the Niam-Niam tribe would go on playing an instrument all day and all night without thinking to leave off to eat or drink." Most of the native dances witnessed by the explorers were of a voluptuous type. One must make allowance for the fact that there was reserve about sexual matters in Europe during a part of the nineteenth century, and Livingstone, as a missionary, could not be expected to approve: but Speke, Du Chaillu, and Fynn were what are called "men of the world", and they too regarded these dances as grossly obscene." "The people lost all control at the sound of the tom-tom; the louder and more energetically the horrid drum is beaten, the wilder are the jumps of the male African, and the more disgustingly indecent the contortions of the women." Every woman was furiously tipsy, and thought it a point of honour to be more indecent that her neighbor." Each tribe had its own traditions in these matters, and one cannot easily distil tribe of what was common to many."

"Evil spirits, often regarded as the souls of the dead, were supposed to mingle in some mysterious way with the affairs of the living, for the purpose of harming them and depriving them of all earthly pleasures. Terror of the spirits was widespread."

"Among the Bakalai too, there was no sympathy for those who were sick or aged and lacked friends to support them. They were driven out of the villages to die in loneliness in the forest. Du Chaillu twice saw old men driven out in this way." "Slaves were treated by members of this group (Western Bantu) of Negrids in Gabon as though their lives were unworthy of consideration, for by native customs the right was accorded to all slave-owners to kill them at will." Under Chaka's rule, as witnessed by Fynn, a movement of a royal finger, just perceptible to his attendants, sufficed to indicate that a man was to be taken away and executed. On the first day of Fynn's arrival at court, ten men were carried off to death, and he soon learnt that executions occurred daily. On one occasion Fynn witnessed the dispatch of sixty boys under the age of twelve years before Chaka had breakfasted. The ordinary method of execution in Zululand was a sudden twisting of the neck, but in one case a man accused of witchcraft was suspended from a tree by his feet and burnt to death by a fire lit below me. Sometimes people were killed by driving a stick into the body through the anus and leaving them to die. On one occasion between four and five hundred women were massacred because they were believed to have knowledge of witchcraft. One of Chaka's concubines was executed for taking a pinch of snuff from his snuff-box. A group of cowherd boys was put to death for having sucked the nipples of cattle. Every village chief was permitted to kill any of his people. Adultery was punished by death for both parties, and even the suspicion of adultery would authorize a husband to kill his wife. The most terrible event of Chaka's reign that was actually witnessed by Fynn followed the illness and death of Nandi (his mother). Universal mourning was immediately ordered. The chiefs and people began to assemble in a crowd estimated at eight thousand. To eat or drink was forbidden; weeping was compulsory. Lamentations followed all night. Those who could not force tears from their eyes - those who were near the river panting for water - were beaten to death by others who were mad with excitement. Toward the afternoon I calculated that not fewer than 7,000 people had fallen in this frightful indiscriminate massacre. Whilst masses were thus employing themselves, Shaka and his chiefs, the latter surrounding him, were tumbling and throwing themselves about, each trying to excel in their demonstrations of grief by alternate fits of howling. Fynn felt as if the whole universe were at that moment coming to an end. During a period of one year after Nandi's death all women found to be pregnant were executed with their husbands.

Du Chaillu writes, "In fact, symptoms of cannibalism stare me in the face whenever I go, and I can no longer doubt. It appeared to be the custom that when a villager was killed or died, his corpse was sent to another Fang village, for sale as food. This seems the proper and usual end of the Fangs'. Unlike other tribes, the Fang had few slaves, partly because they were accustomed to eat prisoners taken in war; but they bought the bodies of slaves from other tribes for eating, paying ivory for them." Schweinfurth was the first European to obtain full information about cannibalism among the Azande. He noticed piles of refuse with fragments of human bones strewn among them; all around were shriveled human feet and hands, hanging on the branches of trees. The Azande made no secret of their use of human flesh as nutriment. They spoke freely on the subject, telling the explorer that no corpses were rejected as unfit for food, unless the person had died of some loathsome skin-disease. Skulls from which flesh and brains had been obtained were exhibited on stakes beside their huts. Any person who died without relatives to protect his body was sure to be devoured in the very district in which he had lived; and in times of war, any member of a conquered tribe was regarded as suitable for eating. Of the various oily and fatty substances employed in cooking, the one in most frequent use was human fat.

There was no written language in any part of the secluded area, and indeed it was found difficult to convey to the native inhabitants the idea of what was meant by it. The Ovambo frankly disbelieved that Galton could express words by writing on paper. The Negrid peoples knew nothing of their history. Among the Rek, a section of the Dinka... all the lives and deeds of men have been long forgotten. The people were without traditions, without history, Speke writes." Knowledge of mathematics was everywhere rudimentary, though there were differences between the tribes in this respect. The Ovaherero seem to have occupied an extreme position in the scale. Galton claimed that though they might possess words for higher numbers, they did not actually make use of any numeral higher than three. When they wished to express four, they used their fingers instead of an appropriate word. The Madi, according to Schweinfurth, only counted up to ten; greater numbers were generally indicated by gestures." It would not appear from the works of the explorers that the Negrids appreciated the independent or primary human value of knowledge about the natural world; or in other words, science (as opposed to technology) may be said to have been almost but not quite non-existent. Livingstone writes of the Bechuana, for instance, No science has been developed, and few questions are ever discussed except those which have an intimate connection with the wants of the stomach. Generalizing more widely he remarks, "All that the Africans have thought of has been present gratification." Fynn, too, tells us that he seldom found any Zulu gifted with the inquisitiveness that makes people interested in knowledge, apart from the possibility of its immediate application to the practical affairs of their lives." These comments are too sweeping, however for application to all the tribes." Du Chaillu writes of the "utter improvidence" of the Gabon tribes. Speke expresses the same idea when he says that the Negro "thinks only for the moment."

A remark of Schweinfurth's about the Monbuttu is representative of many written by the others. "Whilst the women attend to the tillage of the soil and the gathering of the harvest, the men, except they are absent either for war or hunting, spend the entire day in idleness. In the early hours of the morning they may be found under the shade of the oil-palms, lounging at full length upon their carved benches and smoking tobacco. During the middle of the day they gossip with their friends in the cool halls." Baker makes this similar comment,”it was the custom in Unyoro for the men to enjoy themselves in laziness, while the women performed all the labour of the fields. Thus they were fatigued, and glad to rest, while the men passed the night in uproarious merriment." Generalizing about Negrids he says, “There is a lack of industry, a want of intensity of character, a love of ease and luxury." Those who might have been expected to show enterprise in occupying themselves more intelligently seem to have been as deficient as the rest in this respect. At Matesa's palace in Bunyoro, the Wakungu or court officers usually spent their time lounging about on the ground, smoking, chatting, and drinking pombe. Remarks of a similar nature to these are frequent in the books of the explorers, and mere repetition of the same theme would be tedious. It must suffice to say that the failure to advance as quickly towards civilization as certain other races cannot be attributed to day-long devotion to the task of supplying the immediate needs of life.""

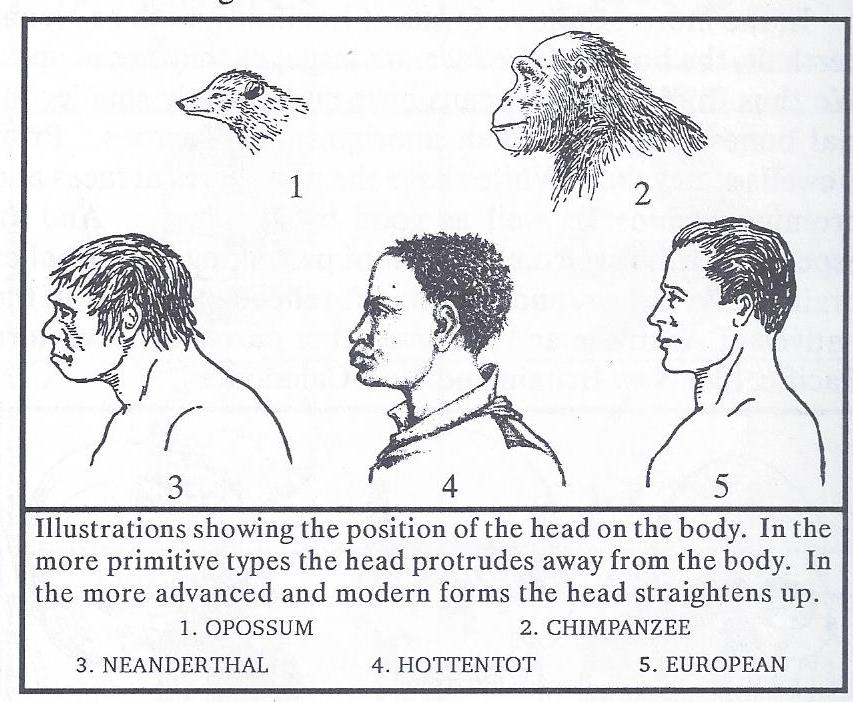

Other Negroid Information. - Baker continues "Broca remarked long ago of the Negro, “In him the bones of the cranium are conspicuously thicker than ours, and have at the same time much greater density; they scarcely contain any diploe, and their resistance is much that they can sustain truly extraordinary blows without breaking." The extreme thickness of the skull and the replacement of diploe by compact bone in Australids has already been mentioned. Pithecanthropus, too, was guarded against heavy blows to the head by the thickness of his cranial walls, and he would have been well fitted to stand up to battering in the boxing ring." A.H. Stone, writing a few years later, made exactly the same point: "Practically all the so-called Negroes of distinction are not real Negroes at all," he claimed; and in another part of the same book, "There can no longer be a question as to the superior intelligence of the mulatto over the Negro - of his higher potential capacity... the Negro masses are almost always led by the mulatto.""

Other seminal books on inner Africa, before they had seen Whites, before iron, before the written word, before all we take for granted today: “The Negroes in Negro-land, by Hilton Rowan Helper, 1868 - (can be found on internet )

THOMAS JEFFERSON

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) was the author of the "Declaration of Independence" and third president of the United States. He founded the Democratic Party, the University of Virginia and the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom. Jefferson orchestrated the Louisiana Purchase and the abolishment of slave trade in the United States. He played a major part in shaping American governmental theory and practice. But most of all Jefferson possessed a revolutionary mentality towards the rights of man. Throughout his life he proclaimed his absolute opposition to the institution of slavery. He considered it to be a scar upon the integrity of mankind and of the United States. Yet, he was by birth a slave holder and he never released his slaves to freedom – He referred to the Africa slave as a wolf by the ears, you could not turn it loose or it will devour America. Jefferson's interests were quite varied and came close to the Renaissance ideal of the universal man. He supported a philosophy of government based on popular sovereignty, and a strict interpretation of the Constitution. He believed that all government should rest upon the consent of the governed. Jefferson had faith in the capacity of the people for self-government, but thought education a prerequisite to efficiency and understanding. He was in favor of "property holding" requirements for the voter, and if alive today he would probably advise strong literacy testing for the opportunity to vote. Jefferson thought an agricultural economy to be superior to an industrial one. He believed "urban" people to be basically corrupt and the small farmer to be the backbone of a strong republic. He believed that any loss of national income from agriculture would be "made up in happiness and permanence of government." He favored strong local government over a larger centralized power - decentralization. He visualized thousands of small localities governed by individuals known to the people. To Jefferson, freedom was not an opportunity to enjoy the labors and sacrifices of a previous generation but a duty to complete the work left undone by their fathers. Jefferson was a lawyer, an architect, a businessman, inventor, politician and a farmer. He was well versed in literature, art, paleontology, ethnology, geography, and botany. Within Mr. Jefferson's "Notes on the State of Virginia", released in 1787, the chapter on "Laws" discusses proposed legislation that would be to the benefit of an on-going concern of a democracy. Although he had not planned on these notes being published to the world, a French language copy had been released without his permission. Many parts were erroneously stated, so he was obliged to release the original version. The "Notes" were originally meant only for the eyes of heads of State within the United States and France.

To emancipate all slaves born after passing the act. The bill reported by the revisors does not itself contain this proposition; but an amendment containing it was prepared to be offered to the legislature whenever the bill should be taken up, and further directing, that they should continue with their parents to a certain age, then be brought up, at the public expense, to tillage, arts or sciences, according to their geniuses, till the females should be eighteen, and the males twenty-one years of age when they should be colonized to such place as the circumstances of the time should render most proper, sending them out with arms, implements of household and of the handicraft arts, seeds, pairs of the useful domestic animals, &c. to declare them a free and independent people, and extend to them our alliance and protection, till they shall have acquired strength; and to send vessels at the same time to other parts of the world for an equal number of white inhabitants; to induce to migrate hither, proper encouragements were to be proposed. It will probably be asked, why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expense of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.

To these objections, which are political, may be added others, which are physical and moral. The first difference which strikes us is that of colour. Whether the black of the Negro resides in the reticular membrane between the skin and scarf-skin itself; whether it proceeds from the colour of the blood, the colour of the bile, or from that of some other secretion, the difference is fixed in nature, and is as real as if its seat and course were better known to us. And is this difference of no importance? Is it not the foundation of a greater or less share of beauty in the two races? Are not the fine mixtures of red and white, the expressions to every passion by greater or less suffusions of colour in the one, preferable to that eternal monotony, which reigns in the countenances, that immoveable veil of black which covers all the emotions of the other race? Add to these, flowing hair, a more elegant symmetry of form, their own judgment in favor of whites, declared by their preference of them, as uniformly as is the preference of the Oran-ootan for the black women over those of his own species (oran-ootan is the chimpanzee kc). The circumstances of superior beauty, is thought worthy attention in the propagation of our horses, dogs, and other domestic animals; why not in that of man? Besides those of colour, figure, and hair, there are other physical distinctions proving a difference of race. They have less hair on the face and body. They secrete less by the kidneys, and more by the glands of the skin, which gives them a very strong and disagreeable odour. This greater degree of transportation renders them more tolerant of heat, and less so of cold, than the whites. Perhaps too a difference of structure in the pulmonary apparatus, which a late ingenious experimentalist has discovered to be the principle regulator of animal heat, may have disabled them from extricating, in the act of inspiration, so much of that fluid from the outer air, or obliged them in expiration, to part with more of it. They seem to require less sleep. A black, after hard labour through the day, will be induced by the slightest amusements to sit up till midnight, or later, though knowing he must be out with the first dawn of the morning.

They are at least as brave, and more adventuresome. But this may perhaps proceed from a lack of forethought, which prevents their seeing a danger till it be present, they do not go through it with more coolness or steadiness than the whites. They are more ardent after their female: but love seems with them to be more an eager desire, than a tender delicate mixture of sentiment and sensation. Their griefs are transient. Those numberless afflictions, which render it doubtful whether heaven has given life to us in mercy or in wrath, are less felt, and sooner forgotten with them. In general, their existence appears to participate more of sensation than reflection. To this must be ascribed their disposition to sleep when abstracted from their diversions, and unemployed in labour. An animal whose body is at rest, and who does not reflect, must be disposed to sleep of course. Comparing them by their faculties of memory, reason, and imagination, it appears to me, that in memory they are equal to whites; in reason much inferior, as I think one could scarcely be found capable of tracing and comprehending the investigation of Euclid; and that in imagination they are dull ,tasteless, and anomalous. It would be unfair to follow them to Africa for this investigation. We will consider them here, on the same stage with whites, and where the facts are not apocryphal on which a judgment is to be formed. It will be right to make great allowances for the difference of condition, of education, of conversation, of the sphere in which they move. Many millions of them have been brought to, and born in America. Most of them indeed have been confined to tillage, to their own homes and their own society: yet many have been so situated, that they might have availed themselves of the conversation of their masters; many have been brought up to the handicraft arts, and from that circumstance have always been associated with the whites. Some have been liberally educated, and all have lived in countries where the arts and sciences are cultivated to a considerable degree, and have had before their eyes samples of the best works from abroad. But never yet could I find that a black had uttered a thought above the level of plain narration; never see even an elementary trait of painting or sculpture. In music they are generally more gifted than the whites with accurate ears for, tuning and time, and they have been found capable of imagining a small catch. Whether they will be equal to the composition of a more extensive run of melody, or of complicated harmony, is yet to be proved. Misery is often the parent of most affecting touches in poetry. Among the blacks is misery enough, God knows, but no poetry. Love is the peculiar oestrum of the poet. Their love is ardent, but it kindles the senses only, not the imagination. Religion indeed has produced a Phyllis Whately, but it could not produce a poet. The compositions published under her name are below the dignity of criticism. The improvement of the blacks in body and mind, in the first instance of their mixture with the whites, has been observed by everyone, and proves that their inferiority is not the effect merely of their condition of life. We know that among the Romans, about the Augustan age especially, the condition of their slaves was much more deplorable than that of the blacks on the continent of America. The two sexes were confined in separate apartments, because to raise a child cost the master more than to buy one. Cato, for a very restricted indulgence to his slaves in this particular, took from them a certain price. But in this country the slaves multiply as fast as the free inhabitants. Their situation and manners place the commerce between the two sexes almost without restraint. The same Cato, on a principle of economy, always sold his sick and superannuated slaves. He gives it as a standing precept to master visiting his farm, to sell his old oxen, old wagons, old tools, old and diseased servants, and everything else become useless. Yet notwithstanding these and other discouraging circumstances among the Romans, their slaves were often their rarest artists. They excelled too in science, insomuch as to be usually employed as tutors to their master's children. But the slaves were the races of the whites. It is not their condition then, but nature, which has produced the distinction. Whether further observation will or will not verify the conjecture, that nature has been less bountiful to them in the endowments of the head, I believe that in those of the heart she will be found to have done them justice. That disposition to theft with which they have been branded, must be ascribed to their situation, and not to any depravity of the moral sense. The man, in whose favor no laws of property exist, probably feels himself less bound to respect those made in favor of others. When arguing for ourselves, we lay it down as a fundamental, that laws, to be just, must give a reciprocation of right: that, without this, they are mere arbitrary rules of conduct, founded in force, and not in conscience: and it is a problem which I give to the master to solve, whether the religious precepts against the violation of property were not framed for him as well as his slaves? And whether the slave may not as justifiably take a little from one, who has taken all from him, as he may slay one who would slay him? That a change in the relations in which a man is placed should change his ideas of moral right and wrong, is neither new, nor peculiar to the colour of the blacks. Homer tells us it was so 2600 years ago.............[Jove fix'd it certain, that whatever day........ Makes man a slave, takes half his worth away.] But the slaves of which Homer speaks were white. Notwithstanding these considerations which must weaken their respect for the laws of property, we find among them numerous instances of the most rigid integrity, and as many as among their better instructed masters, of benevolence, gratitude, and unshaken fidelity. The opinion, that they are inferior in the faculties of reason and imagination, must be hazarded with great diffidence. To justify a general conclusion, requires many observations, even where the subject may be submitted to the Anatomical knife, to Optical glasses, to analysis by fire, or by solvents. How much more then where it is a faculty, not a substance, we are examining; where it eludes the research of all the senses; where the conditions of its existence are various and variously combined; where the effects of those which are present or absent bid defiance to calculation; let me add too, as a circumstance of great tenderness, where our conclusion would degrade a whole race of men from the rank in the scale of beings which their Creator may perhaps have given them. Too our reproach it must be said, that though for a century and a half we have had under our eyes the races of black and of red men, they have never yet been viewed by us as subjects of natural history. I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind. It is not against experience to suppose, that different species of the same genus, or varieties of the same species, may possess different qualifications. Will not a lover of natural history then, one who views the gradations in all the races of animals with the eye of philosophy, excuse an effort to keep those in the department of man as distinct as nature has formed them? This unfortunate difference of colour, and perhaps of faculty, is a powerful obstacle to the emancipation of these people. Many of their advocates, while they wish to vindicate the liberty of human nature, are anxious also to preserve its dignity and beauty. Some of these, embarrassed by the question "What further is to be done with them?" join themselves in opposition with those who are actuated by sordid avarice only. Among the Romans emancipation required but one effort. The slave, when made free, might mix with, without straining the blood of his master. But with us a second is necessary, unknown to history. When freed, he is to be removed beyond the reach of mixture."

Jefferson, the man who originated the statement "All men are created equal" also made a related statement which very few Americans have ever read. He said, "Nothing is more unequal than the equal treatment of unequal people." In conclusion, we must consider the wisdom of Jefferson's words when he stated, "Nothing is written more clearly than the blacks are destined to be free, however, the two races, equally free, cannot live within the same government."

AMERICAN COLONIZATION SOCIETY

Also, during the Jefferson Era, a group of prominent Americans formed the American Colonization Society, organized in 1816. Among the members were Henry Clay, Speaker of the House, and James Madison, fourth president of the United States. The function of the Society was not to denounce slavery but to remove all free black residents from the United States to a Colonization point in Africa. Inspired by the Sierra Leone Company (a previous black "return to Africa" organization), the Society, with grant money from the U.S. government, located Liberia along the coast of Africa as a settlement point for all blacks in the United States. The capital was named Monrovia after James Monroe, President, and another supporter of the project. Apparently, the Society was dedicated to the accomplishment of an all-white America. Henry Clay was pleased with the goals of the Society because America was removing "a useless and pernicious, if not dangerous portion of its population, and of all classes of our population, the most vicious is that of a free colored people."

Jefferson considered the attempt noble, however he realized the limitations of such an enormous project. The Society only settled less than 15,000 blacks to Liberia, so the Society could not even keep pace with the high birth rate of existing free blacks. In 1820 there were about 1.5 million blacks in the U.S., however by 1860, there were almost 4 million. In 1820, the governor of Virginia, Thomas Randolph, attempted legislation to remove all slave youths to Haiti, and thus let the existing population die off naturally. The bill died without discussion. Another problem with the deportation was the staggering cost, an estimated one billion dollars ($600 was the cost of the slaves), and a time when the national debt was in the millions. Jefferson's dream of removing "this blot on our country" and "this great political and moral evil" failed.

HAITI

Haiti 1791: One of the earliest and most marked aggressions by the black race against the white race started in 1791 in Haiti (Santo Domingo). Black slaves and mulattoes rose in revolution against the white ruled Haiti, to secure rights promised to them by the "Declaration of the Rights of Man." By 1793, the United States government predicted that all whites would be expelled from the West Indies and the islands would set up governments of their own. Toussaint Louverture, a former slave, was the leader of the revolution. In 1800, to forestall any danger to the United States that an immediately close black nation could cause, Hamilton drew up a constitution for what he hoped would be an organized republic of Santo Domingo with Louverture as president. It was of importance to the United States to have a friendly Caribbean, as it was important to keep Cuba an ally. In early America, fear of dominance came from France (Napoleon Bonaparte) and Great Britain. However, another faction of the U.S. government had great fears of having such a group of revolutionary former slaves so close to the United States. They viewed it as a threat to the safety of the Southern slave holding states, and specifically a threat to the long term White America. These viewpoints favored a termination of the revolution by whatever means possible. During the Revolution, every single white (thousands) living in Haiti was murdered by the black revolutionaries. To this day, Haiti is the most poverty stricken country in the Western Hemisphere. Its population is 100% black. An interesting footnote to this event was a comment by Napoleon concerning the white/black relationship in Haiti. He said "I am for the whites because I am white. I have no other reason. That one suffices."

ALEXIS de TOCQUEVILLE

Mr. Tocqueville's "Democracy in America" (1835-1840) is quoted. Throughout the book, Tocqueville discusses his views on the tyranny and oppression of the slave state. He leaves no doubt in the mind of the reader that slavery was an abomination hell on earth. And as with other material presented within this writing, he presents interesting observations, perhaps prophecy visions, on the long term effects of the Black arrival on the shores of America. Selected passages are presented below. "As long as the Negro remains a slave, he may be kept in a condition not far removed from that of the brutes; but with his liberty he cannot but acquire a degree of instruction that will enable him to appreciate his misfortunes and to discern a remedy for them. Moreover, there exists a singular principle of relative justice which is firmly implanted in the human heart. Men are much more forcibly struck by those inequalities which exist within the same class than by those which may be noted between different classes. One can understand slavery, but how can one allow several millions of citizens to exist under a load of eternal infamy and hereditary wretchedness? In the North the population of freed Negroes feels these hardships and indignities, but its numbers and its powers are small, while in the South it would be numerous and strong. As soon as it is admitted that the whites and the emancipated blacks are placed upon the same territory in the situation of two foreign communities, it will readily be understood that there are but two chances for the future: the Negros and the Whites must either wholly part (separate kc) or wholly mingle. I have already expressed my conviction that the latter is highly improbable. Nothing is more clearly written in the book of destiny than the emancipation of the blacks; and it is equally certain, that the two races will never live in a state of equal freedom under the same government, so insurmountable are the barriers which nature, habit, opinion have established between them. I do not believe the white and black races will ever live in any country upon an equal footing. But I believe the difficulty to be still greater in the United States than elsewhere. An isolated individual may surmount the prejudices of religion, of his country, or of his race; and if this individual is a king, he may affect surprising changes in society; but a whole people cannot rise, as it were, above itself. A despot who should subject the Americans and their former slaves to the joke might perhaps succeed in commingling their races; but as long as the American democracy remains in the head of affairs, no one will undertake so difficult a task and it may be foreseen that the freer the white population of the United States becomes, the more isolated will it remain. The pride of origin, which is natural to the English, is singularly augmented by the personal pride that democratic liberty fosters among the Americans; the white citizens of the United States is proud of his race and proud of himself. But if the whites and the Negroes do not intermingle in the North of the Union, how should they mix in the South? Can it be supposed for an instant that an American of the Southern states, placed, as he must forever be, between the white man, with all his physical and moral superiority, and the Negro, will ever think of being confounded with the latter? The Americans of the Southern states have two powerful passions which will always keep them aloof; the first is the fear of being assimilated to the Negros, their former slaves; and the second, the dread of sinking below the whites, their neighbors. If I were called upon to predict the future, I should say that the abolition of slavery in the South will in the common course of things, increase the repugnance of the white population for the blacks. I base this opinion upon the analogous observation I have already made in the North. I have remarked that the white inhabitants of the North avoid the Negros with increasing care in proportion as the legal barriers of separation are removed by the legislature; and why should not the same result take place in the South? In the North the whites are deterred from intermingling with the blacks by an imaginary danger; in the South, where the danger would be real, I cannot believe that the fear would be less.

If, on the other hand, it be admitted (and the fact is unquestionable) that the colored population perpetually accumulate in the extreme South and increase more rapidly than the whites; and if on the other hand, it be allowed that it is impossible to foresee a time at which the whites and the blacks will be so intermingled as to derive the same benefits from society, must it not be inferred that the blacks and the whites will, sooner or later, come to open strife in the Southern states? But if it be asked what the issue of the struggle is likely to be, it will readily be understood that we are here left to vague conjectures. The human mind may succeed in tracing a wide circle, as it were, which includes the future; but within that circle chance rules, and eludes all our foresight. In every picture of the future there is a dim spot which the eye of the understanding cannot penetrate. It appears, however, extremely probable that in the West Indies islands the white race is destined to be subdued, and upon the continent the blacks. In the West Indies the white planters are isolated amid an immense black population; on the continent the blacks are placed between the ocean and an innumerable people, who already extend above them, in a compact mass, from the icy confines of Canada to the frontiers of Virginia, and from the banks of the Missouri to the shores of the Atlantic. If the white citizens of North America remain united, it is difficult to believe the Negroes will escape the destruction which menaces them; they must be subdued by want or by the sword. But the black population accumulated along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico have a chance of success if the American Union should be dissolved when the struggle between the two races begins. The Federal tie once broken, the people of the South could not rely upon any lasting succor from their Northern countrymen. The latter are well aware that the danger can never reach them; and unless they are constrained to march to the assistance of the South by a positive obligation, it may be foreseen that the sympathy of race will be powerless. Yet, at whatever period the strife may break out, the whites of the South, even if they are abandoned to their own resources, will enter the list with an immense superiority of knowledge and the means of warfare; but the blacks will have numerical strength and the energy of despair upon their side, and these are powerful resources to men who have taken up arms. The fate of the white population of the Southern states will perhaps be similar to that of Moors of Spain. After having occupied the land for centuries, it will perhaps return by degrees to the country whence its ancestors came and abandon to the Negroes the possession of a territory which Providence seems to have destined for them, since they can subsist and labor in it more easily than the whites. The danger of a conflict between the white and the black inhabitants of the Southern states of the Union (is inevitable) perpetually haunts the imagination of the Americans, like a painful dream. The inhabitants of the North make it a common topic of conversation, although directly they have nothing to fear from it; but they vainly endeavor to devise some means of obviating the misfortunes which they foresee. In the Southern states the subject is not discussed: the planter does not allude to the future in conversing with strangers; he does not communicate his apprehensions to his friends; he seeks to conceal them from himself. But there is something more alarming in the tacit forebodings of the South that in the clamorous fears of the North. This all-pervading disquietude has given birth to an undertaking as yet but little known, which, however, may change the fate of a portion of the human race." Tocqueville further states "I am obligated to confess that I do not regard the abolition of slavery as a means of warding off the struggle of the two races in the Southern states. The Negroes may long remain slaves without complaining; but if they are once raised to the level of freemen, they will soon revolt at being deprived of almost all their civil rights; and as they cannot become the equals of the whites, they will speedily show themselves as enemies. In the North everything facilitated the emancipation of the slaves, and slavery was abolished without rendering the free Negroes formidable, since their number was too small for them ever to claim their rights. But such is not the case in the South. The question of slavery was a commercial and manufacturing question for the slave-owners in the North; for those of the South it is a question of life and death. God forbid that I should seek to justify the principle of Negro slavery, however. When I contemplate the condition of the South, I can discover only two modes of action for the white inhabitants of those States: namely, either to emancipate the Negroes and to intermingle with them, or, remaining isolated from them, to keep them in slavery as long as possible. All intermediate measures seem to be likely to terminate, and that shortly, in the most horrible of civil wars and perhaps in the extirpation of one or the other of the races. Such is the view that the Americans of the South take of the question, and they act consistently with it. As they are determined not to mingle with the Negroes, they refuse to emancipate them. If liberty be refused to the Negroes of the South, they will in the end forcibly seize it for themselves; if it be given, they will before long abuse it."

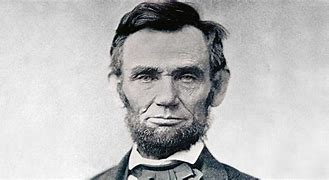

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) was our 16th president of the United States and at one of the most crucial times in the history of the United States, the time of the War of Secession. For some, he is considered the emancipator of the slaves and school children usually considered him and Washington as their favorite presidents. Some historians consider him to be one of the greatest presidents; some believe him to have been the greatest. Since his death, Lincoln has become a folk hero: Honest Abe, Great Emancipator. He has become to be known throughout the world as a symbol of national unity, democracy, and emancipation. Lincoln is often portrayed as an enemy of the South, yet his reconstruction plans were to "Treat them as if they had never left". Lincoln was murdered shortly before these plans were placed in motion.

On August 14, 1862, President Lincoln made an "Address on the Colonization to a Deputation of Negroes. " His address is part of historical record and is detailed in the following paragraphs. "This afternoon the President of the United States gave audience to a Committee of colored men at the White House. They were introduced by the Rev. J. Mitchell, Commissioner of Emigration. E.M. Thomas, the Chairman, remarked that they were there by invitation to hear what the Executive had to say to them. Having all been seated, the President, after a few preliminary observations, informed them that a sum of money had been appropriated by Congress, and placed at his disposition for the purpose of aiding the colonization in some country of the people, or a portion of them, of African descent, thereby making it his duty, as it had for a long time been his inclination, to favor that cause; and why, he asked, should the people of your race be colonized, and where? Why should they leave this country? This is, perhaps the first question for proper consideration. You and we are different races. We have between us a broader difference than exists between almost any other two races. Whether it is right or wrong I need not discuss, but this physical difference is a great disadvantage to us both, as I think your race very greatly, many of them by living among us, while ours suffer from your presence. In a word we suffer on each side. If this is admitted, it affords a reason at least why we should be separated. You here are freemen I suppose. A voice: Yes sir. The President-Perhaps you have long been free, or all your lives. Your race are suffering, in my judgment, the greatest wrong inflicted on any people. But when you cease to be slaves, you are yet far removed from being placed on an equality with the white race. You are cut off from many of the advantages which the other race enjoy. The aspiration of men is to enjoy equality with the best when free, but on this broad continent, not a single man of your race is made the equal of a single man of ours. Go where you are treated the best, and the ban is still upon you. I do not propose to discuss this, but to present it as a fact with which we have to deal. I cannot alter it if I would. It is a fact, about which we all think and feel alike, me and you. We look to our condition, owning to the existence of the two races on this continent. I need not recount to you the effects upon white men, growing out of the institution of Slavery. I believe in its general evil effects on the white race. See our present condition-the country engaged in war-our white men cutting one another's throats, none knowing how far it will extend; and then consider what we know to be the truth. But for your race among us there could not be war, although many men engaged on either side do not care for you one way or the other. Nevertheless, I repeat, without the institution of Slavery and the colored race as a basis, the war could not have an existence. It is better for us both, therefore, to be separated. I know that there are free men among you, who even if they could better their condition are not as much inclined to go out of the country as those, who being slaves could obtain their freedom on this condition. I suppose one of the principle difficulties in the way of colonization is that the free colored man cannot see that his comfort would be advanced by it. You may believe you can live in Washington or elsewhere in the United States the remainder of your life (as easily), perhaps more so than you can in any foreign country, and hence you may come to the conclusion that you have nothing to do with the idea of going to a foreign country. This is an extremely selfish view of the case. But you ought to do something to help those who are not as fortunate as yourselves. There is an unwillingness on the part of our people, harsh as it may be, for you free colored people to remain with us. Now if you could give a start to white people, you would open a wide door for many to be made free. If we deal with those who are not free at the beginning, and whose intellects are clouded by Slavery, we have very poor materials to start with. If intelligent colored men, such as are before me, would move in this matter, much might be accomplished. It is exceedingly important that we have men at the beginning capable of thinking as white men, and not those who have been systematically oppressed. There is much to encourage you. For the sake of your race you should sacrifice something of your present comfort for the purpose of being as grand in that respect as the white people. It is a cheering thought throughout life that something can be done to ameliorate the condition of those who have been subject to the hard usage of the world. It is difficult to make a man miserable while he feels he is worthy of himself, and claims kindred to the great God who made him. In the American Revolutionary war sacrifices were made by men engaged in it; but they cheered by the future. Gen. Washington himself endured greater physical hardships than if he had remained a British subject yet he was a happy man, because he was engaged in benefiting his race-something for the children of his neighbors, having none of his own.

The colony of Liberia has been in existence a long time. In a certain sense it is a success. The old President of Liberia, Roberts, has just been with me-the first I ever saw him. He says they have within the bounds of that colony between 300,000 and 400,000 people, or more than in some of our old States, such as Rhode Island or Delaware, or in some of our newer States, and less than in some our larger ones. They are not all American colonists, or their descendants. Something less than 12,000 have been sent thither from this country. Many of the original settlers have died, yet, like people elsewhere, their offspring outnumber those deceased.

The question is if the colored people are persuaded to go anywhere, why not there? One reason for an unwillingness to do so is that some of you would rather remain within reach of the country of your nativity. I do not know how much attachment you may have toward your race. It does strike me that you have the greatest reason to love them. But still you are attached to them at all events. The place I am thinking about having for a colony is in Central America. It is nearer to us than Liberia-not much more than one-fourth as far as Liberia, and within seven days run by steamers. Unlike Liberia it is on a great line of travel-it is a highway. The country is a very excellent one for any people, and with great natural resources and advantages, and especially because of the similarity of climate with your native land-thus being suited to your physical condition. The particular place I have in view is to be a great highway from the Atlantic or Caribbean Sea to the Pacific Ocean, and this particular place has all the advantages for a colony. On both sides there are harbors among the finest in the world. Again, there is evidence of very rich coal mines. A certain amount of coal is valuable in any country, and there may be more than enough for the wants of the country. Why I attach so much importance to coal is, it will afford an opportunity to the inhabitants for immediate employment till they get ready to settle permanently in their homes. If you take colonists where there is no good landing, there is a bad show; and so where there is nothing to cultivate, and of which to make a farm. But if something is started so that you can get your daily bread as soon as you reach there, it is a great advantage. Coal land is the best thing I know of which to commence an enterprise. To return, you have been talked to upon the subject, and told that a speculation is intended by gentlemen, who have an interest in the country, including the coal mines. We have been mistaken all our lives if we do not know whites as well as blacks look to their self-interest. Unless among those deficient of intellect everybody you trade with makes something. You meet with these things here as elsewhere. If such persons have what will be an advantage to them, the question is whether it cannot be made of advantage to you. You are intelligent, and know that success does not as much depend on external help as on self-reliance. Much, therefore, depends upon yourselves. As to the coal mines, I think I see the means available for your self-reliance. I shall, if I get a sufficient number of you engaged, have provisions made that you not be wronged. If you will engage in the enterprise I will spend some of the money entrusted to me. I am not sure you will succeed. The Government may lose the money, but we cannot succeed unless we try; but we think, with care, we can succeed. The political affairs in Central America are not in quite as satisfactory condition as I wish. There are contending factions in that quarter; but it is true all the factions are agreed alike on the subject of colonization, and want it, and are more generous that we are here. To your colored race they have no objections. Besides, I would endeavor to have you made equals, and have the best assurance that you should be the equals of the best. The practical thing I want to ascertain is whether I can get a number of able-bodied men, with their wives and children, who are willing to go, when I present evidence of encouragement and protection. Could I get a hundred tolerably intelligent men, with their wives and children, to "cut their own fodder", so to speak? Can I have fifty? If I could find twenty-five able-bodied men, with a mixture of women and children, good things in the family relation, I think I could make a successful commencement. I want you to let me know whether this can be done or not. This is the practical part of my wish to see you. These are subjects of very great importance, worthy of a month's study, [instead] of a speech delivered in an hour. I ask you then to consider seriously not pertaining to yourselves merely, nor for your race, and ours, for the present time, but as one of the things, if successfully managed, for the good of mankind-not confined to the present generation, but as "From age to age descends the lay, To millions yet to be, Till far its echoes roll away, Into eternity."

The above is merely given as the substance of the President's remarks. The Chairman of the delegation briefly replied that "they would hold a consultation and in a short time give an answer." The President said: "Take your full time-no hurry at all." The delegation then withdrew." Shortly after the meeting the delegation rejected Lincoln's proposal.

|The author W.E. Du Bois, was the first Negro Ph.D. to graduate from Harvard. He later taught history and economics at Atlanta University. He was one of the NAACP founders (1910). In 1961, Du Bois joined the communist party in Ghana. Shortly thereafter he died (1963) a citizen of Ghana. He was an advocate of violence concerning economic and social equality for the Negro and wrote of the colored world: "These nations and races composing as they do a vast majority of humanity, are going to endure this treatment just as long as they must and not a moment longer. Then they are going to fight, and the War of the Color Line will outdo in savage inhumanity any war this world has yet seen. For colored folk have much to remember and they will not forget."

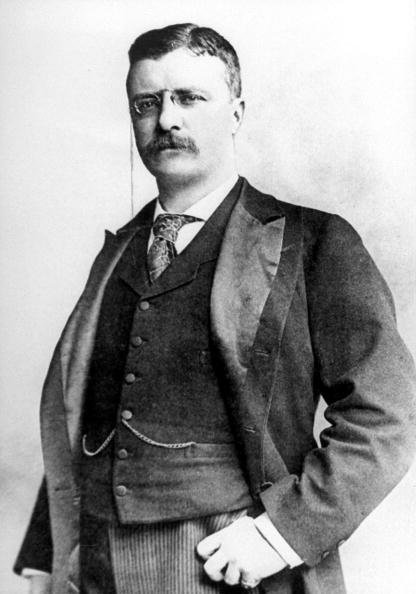

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

"The difference between what can and what cannot be done by law is well exemplified by our experience of which Mr. Watson must have ample practical knowledge. The Negroes were formerly held in slavery. This was wrong which legislation could remedy, and which could not be remedied except by legislation. Accordingly they were set free by law. This having been done, many of their friends believed that in some way, by additional legislation, we could at once put them on an intellectual, social and business equality with the whites. The effort has failed completely."

"Laziness and shiftlessness, these, and above all, vice and criminality, of every kind, are evils more potent for harm to the black race than all acts of oppression of white men put together." "Every colored man should realize that the worst enemy of his race is the negro criminal, and above all the negro criminal who commits the dreadful crime of rape; and it should be felt as in the highest degree and offense against the whole country, and against the colored race in particular, for a colored man to fail to help the officers of the law in hunting down with all possible earnestness and zeal every such infamous offender. Moreover, in my judgment, the crime of rape should always be punished with death, as is the case with murder; assault with intent to commit rape should be a capital crime, at least in the discretion of the court; and provision should be made by which the punishment may follow immediately upon the heels of the offense; while the trial should be so conducted that the victim need not be wantonly shamed while giving testimony, and that the least possible publicity shall be given to the details."

The negro slaves formed a very large portion of the town's [New York City] population, at times, nearly half - for over a century after it was founded; then they gradually began to dwindle in numbers compared to the whites, for although they were retained as household servants, it was found that they were not fitted for manual and agricultural labor, as in the Southern colonies. During the first half of the 18th century they were still very numerous, and were for the most part of African birth being fresh from the holds of the Guinea slavers; they were brutal, ignorant savages, and the whites were in constant dread of a servile insurrection. In 1712 this fear was justified, at least partially, for in that year the slaves formed a wild, foolish plot to destroy all the whites; and some forty of them attempted to put it into execution. Armed with every kid of weapon, they met at midnight in an orchard on the outskirts of the town, set fire to a shed, and assaulted those who came running up to quell the flames. In this way they killed nine men and wounded some others, before the alarm was given and the soldiers from the fort approaching, put them to flight. They fled to the forests in the northern part of the island; but the militia, roused to furious anger, put sentries at the forts, and then hunted down the renegade Negroes like wild beasts. Six, in their despair, slew themselves; and twenty-one of those who were captured were shot, hung or burned at the stake.

A perfectly stupid race can never rise to a very high plane; the Negro, for instance, has been kept down as much by lack of intellectual development as by anything else; but the prime factor in the reservation of a race is its power to attain a high degree of social efficiency. Love of order, ability to fight well and breed well, capacity to subordinate the interests of the individual to the interests of the community, these and similar rather humdrum qualities go to make up the sum of social efficiency.

I have not been able to think out any solution of the terrible problem offered by the presence of the negro on this continent, but of one thing I am sure, and that is that inasmuch as he is here and can neither be killed nor driven away, the only wise and honorable and Christian thing to do is treat each black man and each white man strictly on his merits as a man, giving him no more and no less than he shows himself worthy to have."

Roosevelt also stated most Negroes were "like children, with a grasshopper inability for continuity of thought and realization of the future." "They would often act with an inconsequence that was really puzzling. Dog-like fidelity, preserved in for months, would be ended by a fit of resentment at something unknown, or by a sheer volatility which made them abandon their jobs when it was more to their detriment than to ours. They appreciated justice, but they were neither happy nor well behaved unless they were under authority; weakness toward them was even more ruinous than harshness and over-severity."

LOTHROP STODDARD, A.M. Ph.D. (HARVARD)

Stoddard (in the 1920 publication of "The Rising Tide of Color") discusses the brown population, and Islam the religion of many of these Moslems. The brown world, as he defines it is the Mediterranean area, Arabia, Turkey, India, Northern Africa, the Middle East, etc. He states "Islam is even now an enormous power, full of self-sustaining vitality, with a surplus for aggression; and a struggle with its combined energies would be deadly indeed."

A book published by the 1907 Egyptian leader states "The contact of Europe on the East has caused us both much good and much evil, from the moral and political point of view. Exhausted by long struggle, enervated by a brilliant civilization, the Moslem peoples inevitably fell into a malaise, but they are not stricken, they are not dead!"

Stoddard states "The proselyting power of Islam is extraordinary, and its hold upon its votaries is even more remarkable. Throughout history there has been no single instance where a people, once become Moslem, has ever abandoned the faith. This extreme tenacity of Islam, this ability to keep its hold, once it has got a footing, under all circumstances short of downright extirpation, must be borne in mind when considering the future of regions where Islam is today advancing. Islam is, in fact, the intimate link between the brown and black worlds.”

Stoddard now discusses that black world. The black is of course, African. Stoddard states, "Still, whatever may be the destiny of these transplanted black folk, the black man's chief significance, from the world aspect, must remain bound up with great nucleus of negro population in the African homeland. The black man is, indeed, sharply differentiated from the other branches of mankind. His outstanding quality is superabundant animal vitality. In this he easily surpasses all other races. To it he owes his intense emotionalism. To it, again, is due his extreme fecundity, the Negro being the quickest of breeders. This abounding vitality shows in many other ways, such as the Negro’s ability to survive harsh conditions of slavery under which other races have soon succumbed. Lastly, in ethnic crossings, the Negro strikingly displays his prepotency, for black blood, once entering a human stock, seems never really bred out again. Negro fecundity is a prime factor in Africa's future. In the savage state which until recently prevailed, black multiplication was kept down by a wide variety of checks. Both natural and social causes combined to maintain an extremely high death-rate. The Negro’s political ineptitude, never rising above the tribal concept, kept black Africa's a mosaic of peoples, warring savagely among themselves. Since thee establishment of white political control, however these checks on black fecundity are no longer operative. The white rulers fight filth and disease, stop tribal wars, and stamp out superstitious abominations. In consequence, populations increase by leaps and bounds, the latent possibilities being shown in the native reservations in South Africa, where tribes have increased as much as tenfold in fifty or sixty years." Stoddard asks the question about the long term domination over the black by the white. He states "the blacks have no historical past. Never having evolved civilizations of their own, they are practically devoid of that accumulated mass of beliefs, thoughts, and experiences which render Asiatic so impenetrable and so hostile to white influences. Although the white race displays sustained constructive power to an unrivalled degree, particularly in its Nordic branches, the brown and yellow peoples have contributed greatly to the civilization of the world and have profoundly influenced human progress. The Negro, on the contrary, has contributed virtually nothing

The black race has never shown real constructive power. It has never built up a native civilization. Such progress as certain Negro groups have made has been due to external pressure and has never long outlived that pressure's removal, for the Negro, when left to himself, as in Haiti and Liberia, rapidly reverts to his ancestral ways. The Negro is a facile, even eager, imitator; but there he stops. He adopts; but he does not adapt, assimilate, and give forth creatively again.

The whole history testifies to this truth. As the Englishman Meredith Townsend says: "None of the black races whether negro or Australian, have shown within the historic time the capacity to develop civilization. They have never passed the boundaries of their own habitats as conquerors, and never exercised the smallest influence over peoples not black. They have never founded a stone city, have never built a ship, have never produced a literature, have never suggested a creed....There seems to be no reason for this except race.

This lack of constructive originality, however, renders the Negro extremely susceptible to external influences. The negro, having not past, welcomes novelty." Stoddard then mentions the "naturally brave" blacks and its possible devious use given the implant of a powerful novelty/cause of those less than scrupulous power seekers. "The rapid spread of militant Mohammedanism among the savage tribes to the north of the equator is a serious factor in the fight for racial supremacy in Africa. With a very few exceptions the colored races of Africa are preeminently fighters. To them the law of the stronger is supreme; they have been conquered, and in turn they conquered. To them, the fierce, warlike spirit inherent in Mohammedanism is infinitely more attractive than is the gentle, peace-loving, high moral standard of Christianity: hence, the rapid headway the former is making in central Africa, and the certainty that it will soon spread to the south.

In so far as he is Christianized, the Negro savage instincts will be restrained and he will be disposed to acquiesce in white tutelage. In so far as he is Islamized, the Negro’s warlike propensities will be inflamed. He further states, "Unless, then, every lesson of history is to be disregarded, we must conclude that black Africa is unable to stand alone. The black man's numbers may increase prodigiously and acquire alien veneers, but the black man's nature will not change. Black unrest may grow and cause much trouble. Nevertheless, the white man must stand fast in Africa. No black "renaissance" impends, and Africa, if abandoned by the whites, would merely fall beneath the onset of the browns. And that would be a great calamity. The brown peoples, of themselves, do not directly menace white race-areas, while Pan-Islamism is at present an essentially defensive movement. But Islam is militant by nature, and the Arab is a restless and warlike breed. Pan-Islamism once possessed of the Dark Continent and fired by militant zealots, might forge black Africa into a sword of wrath, the executor of sinister adventures. In short, the real danger to white control of Africa lies not in brown attack or black revolt, but in possible white weakness through chronic discord within the white world itself."

ADOLPH HITLER

It does not dawn upon this depraved bourgeois world that here one has actually to do with a sin against all reason; that it is a criminal absurdity to train a born half-ape until one believes a lawyer has been made of him, while millions of members of the highest culture race have to remain in entirely unworthy positions; that it is a sin against the will of the eternal Creator to let hundreds and hundreds of thousands of His most talented beings degenerate in the proletarian swamp of today, while Hottentots and Zulu Kafirs are trained for intellectual vocations. For it is training, exactly as that of the poodle, and not a scientific "education". The same trouble and care, applied to intelligent races, would fit each individual a thousand times better for the same achievements.

FRANCIS PARKER YOCKEY

From "Imperium" (1946) the Negro in America. "The population of America only consists now of a bare majority that is indisputable American racially, spiritually, nationally. The other half consists of Negroes, Jews, unassimilated South-eastern Europeans, Mexicans, Chinese, Japanese, Siamese, Levantines, Slavs and Indians. The Slavic groups are assailable by the American race, but the process has been artificially held up by the intervention of Culture-distortion."

To a finance-capitalist, however, a Negro merely represents "cheap labor", of a prospect for a small loan. The Master of Money knows nothing of Nation, People, Race, and Culture. He is a "realist" which means, on the primitive-intellectual level, that he regards everything which is as the sum total of Reality. Actually, of course, that which is represents a stage already passed, an Idea already accomplished.

True Reality is the Future at work, for this is the impetus of events. Thus no Money-thinker would ever think two or three generations into the future, for he regards larger conditions as stable, even though he seeks instability in immediate conditions.

The converting of the Negro into a wage slave has demoralized him completely, made him into a discontented proletarian, and created in him a deep racial bitterness. The soul of the Negro remains primitive and childlike in comparison with the nervous and complicated soul of Western man, accustomed to thinking in terms of money and civilization. The result is that the Negro has become a charge of white society.

Social diseases are general among this race, and the hospitals as well as the penitentiaries deal with highly disproportionate numbers of Negroes. Primitive violence is natural to the Negro, and the sense of social disgrace is lacking in him in connection with crimes.